Kew Green

Conservation Area Appraisal

Conservation area no.2

Kew Green

Contents

Part 1: Introduction

Outline of Purpose

The principle aims of Conservation Area Appraisals are to:

- Describe the architectural and historic character and appearance of the area, which will assist applicants in making successful planning applications, and decision makers in assessing planning applications;

- Raise public interest and awareness of the special character of their area;

- Identify the positive features which should be conserved, as well as the negative features which indicate scope for future enhancements.

It is important to note that no Appraisal can be completely comprehensive, and the omission of a particular building, feature, or open space should not be taken to imply that it is of no interest.

This document has been produced using the guidance set out by Historic England in the 2019 publication ‘Conservation Area Appraisal, Designation and Management: Historic England Advice Note 1 (Second Edition)’.

This document will be a material consideration when assessing planning applications.

What is a Conservation Area?

The statutory definition of a conservation area is an ‘area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’. The power to designate conservation areas is given to local authorities through the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 (Sections 69 to 78).

Once designated, proposals within a conservation area become subject to local conservation policies set out in the Council’s Local Plan and national policy outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF).

Our overarching duty, as set out in the Act, it to preserve and/or enhance the historic or architectural character or appearance of the conservation area.

What is an Article 4 Direction?

An Article 4 Direction is made by the local planning authority. It restricts the scope of permitted development rights either in relation to a particular area or site, or a particular type of development anywhere in the authority's area. The Council has powers under Article 4 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 2015 to remove permitted development rights.

Article 4 Directions are used to remove national permitted development rights only in certain limited situations where it is necessary to protect local amenity or the wellbeing of an area. An Article 4 Direction does not prevent the development to which it applies, but instead requires that planning permission is first obtained from the Council for that development. View further information about Article 4 Directions to check if any permitted developments rights in relation to a particular area/site or type of development apply in your area.

Buildings of Townscape Merit

Buildings of Townscape Merit (BTMs) are buildings, groups of buildings, or structures of historic or architectural interest, which are locally listed due to their considerable local importance. The policy, as outlined in the Council’s Local Plan, sets out a presumption against the demolition of BTMs unless structural evidence has been submitted by the applicant, and independently verified at the cost of the applicant. Locally specific guidance on design and character is set out in the Council’s Buildings of Townscape Merit Supplementary Planning Document which applicants are expected to follow for any alterations and extensions to existing BTMs, or for any replacement structures.

Designation and Adoption Dates

Kew Green Conservation Area was designated in 1969. The original area of designation was the Green itself and the riverside. In 1982 the conservation area was extended southwards to protect the approach along Kew Road, and a small area to the east of the railway bridge; in 1988 it was again extended to include the residential streets to the east of the Green.

Following approval by the Environment, Sustainability, Culture and Sports Committee at its meeting on Monday 3rd July 2023 it was agreed to carry out a public consultation on this Appraisal between Monday 18th September and Friday 27th October 2023.

This Appraisal was adopted on 8th February 2024.

Archaeological Priority Areas

An Archaeological Priority Area (APA) is an established location where there is strong known archaeological interest or a particular potential for future discoveries. The local plans for the London boroughs describe APAs. They provide guidance for putting national and local planning principles into practise so that archaeological interest is recognised and preserved.

Historic England updated the Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal for the London Borough of Richmond in March 2022: London Borough of Richmond Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal

Kew Green Conservation Area is under two priority areas. The Kew Gardens APA is a Tier I APA because it covers a historic royal park that has been designated as a World Heritage Site and a Grade I Registered Historic Park and Garden.

Kew Green is classified as Tier 2 as it covers a historic / post-medieval settlement of particular interest because of the historical association with the royal palaces at Richmond and Kew.

The Kew Green APA’s extent is defined by the Green and historic settlement (including numerous listed buildings) fronting it as depicted on historic maps. It falls within the buffer zone of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew World Heritage Site and is associated with the adjacent Kew Gardens and Thames Riverside APAs.

Surveys have revealed archaeological remains in both areas. Along the Kew Towpath Embankment, the remains of a timber drain, a jetty and a concrete wall at the base of the river wall were identified. Around St Anne’s Church, archaeological remains of two earlier phases of the boundary wall showing alterations to the church building in 1805 and 1837 were found; a brick-built burial vault was recorded with the earliest definite burial dating to 1813. The owners of the vault were the Hobbs family of Kew. Disarticulated and in-situ human remains were observed in trenching in the south porch area.

Map of the conservation area

Summary of Special Interest

The Conservation Area was designated in 1969 and was among the first ones to be designated in the borough. Kew Green has a history of settlement dating back to at least the 16th century, with potential for archaeological remnants reflective of this early history.

The area was developed as a high-status residential neighbourhood with royal associations. It was not a typical rural village, as it didn't have a church until the 18th century, and the nobility used the houses for short stays.

The principal reason for designation of the area is the combination of historic open spaces with high-quality historic buildings addressing these spaces. The Green is an important gateway to the borough as it opens out from Kew Bridge and retains and enhances its quality as the setting to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew World Heritage Site (hereafter referred to as ‘Kew Gardens’). The more recently designated extensions have a character of their own, but from within these areas, the influence of the Green is strong, and glimpses into their smaller scale-spaces from the Green enhance their character.

The high proportion of open and green spaces is a key element of the character and appearance of the Conservation Area. The Green is a triangular shaped open space with a strong semi-rural character. It provides an important green setting to the area in conjunction with Kew Gardens, Thames Riverside, Kew Pond and other open spaces like the recreation ground. The long views across the Green and its domestic townscape scale, allows appreciation of its historic form and the richness of built form which surrounds it, adding greatly to the area's significance. There is a general sense of cohesion to the built form surrounding the open spaces in terms of scale and form. However, the area presents a rich variety of building ages and architectural treatment which illustrate the layers of history to the area and its gradual development from a royal rural settlement to a bustling residential area. This adds greatly to its historic significance and brings visual interest and variety to the streetscape.

The significance of Kew Green is closely historically linked with Sheen and Kew palaces. The buildings around the Green are excellent examples of the architecture of the 17th-18th centuries. They were used by the upper classes and subsequently adapted and renovated in each period to be in fashion.

Historic Development

Prehistoric and Saxon Kew

The earliest known occupation in the area is of prehistoric origin, and several finds from the local community have been made on both banks of the River Thames. For centuries it was the lowest point at which the river could be regularly crossed on foot. Although it is believed, based on research and records, the Great Ford at Kew features in Caesar’s Gallic Wars of 54 BC as “a fenced and impenetrable crossing for the invading Romans”, it is yet not confirmed.

The name Kew derived from the Saxon word cayho, which means a quay on a spur of land. It was not until 1314 that Kew is named in any record, but the general use of Kew started in the 17th century. During the Saxon period, in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of 1016, the area is described as the site of a great battle with the Danes.

13th, 14th and 15th centuries

Sheen Manor was built during the 13th century, which began to draw new, higher status individuals to visit and settle in the area, though many would initially stay temporarily, returning to London. The first record of Kew’s residents, however, are mentioned in population records, where five workers of Sheen Manor appear in a document in 1664.

The earliest crossings of the River Thames at Kew were made on foot, with a ford being superseded much later by a ferry. During that period, the people relied almost entirely on the ferry to cross the river. A physical connection between Kew to the other side of the river was not established until the construction of the first bridge in 1758.

Sheen Manor

The Sheen Manor was built by Edward I in 1299. Years later, Edward III, who was attracted to the hunting in the area, turned the Manor into a Palace using the building as a refuge from London. Afterwards, Richard II demolished the Palace to the ground after as his wife died there of plague in 1394. Later, Henry VII decided to rebuilt Sheen Palace in 1501 and this became his favourite palace. He renamed it after his Yorkshire earldom of Richmond and subsequently the palace became known as Richmond Palace.

Figure 1: A view of Richmond Palace (published in 1765, but depicting the palace at an earlier date)

16th, 17th and 18th centuries

The Green, as a triangular open space, has been recorded since 1649, where a Parliamentary Survey of Richmond described as it 'a piece of common or unenclosed ground called Kew Green, lying within the Township of Kew, containing about 20 acres.

The land to the east of the Green formerly belonged to Merton Abbey. The dissolution of the abbey in 1538 resulted in the property becoming a private residence for the heirs of Miss Elizabeth Doughty of Doughty House on Richmond Hill. In 1816, the Priory Estate was constructed in Gothic style by the architect J.B. Papworth. The estate had a Gothic chapel, a room for refreshments and a library. The estate comprised 16 acres, including the main building and two cottages. It was demolished during the 19th century, though the name was retained for subsequent development.

According to the Hearth Tax Returns of 1664, a property tax dating from the medieval period, there were five major estates around the Green: Kew Farm, The Dutch House, Kew Park and Mr Mounteney’s.

In 1703, Kew had 34 dwellings and 153 people living in them, based on the data from the Richmond Manor records. Most of the houses were cottages, with six or seven houses for the nobility recorded.

The Kew area started to acquire characteristics of an English village during the 17th century, but did not have any church, as during this period the area was generally only used by the court during the week. Richmond Palace was demolished in stages for ten years, starting in 1649, and Kew Palace was constructed in 1639.

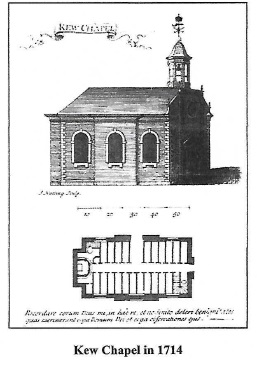

Kew was changing greatly from its Tudor settlement, replacing the cottages with the houses we see today. As villagers started to live in Kew permanently, there was an increased need for a local church, with the nearest located in Kingston, and many could not afford to travel there every Sunday. In 1710 a group of locals petitioned Queen Anne for permission to build a church in the village. During that period the Green was still Crown land, therefore, Queen Anne offered a piece of land and £100 towards the cost. The building was plain, simple, and small and on 12 May 1714, the little chapel was diplomatically dedicated to St Anne.

The alterations that the Green has undergone were more typically related to its use. On older maps, such as London 1734 by John Roque, it can be observed that the area was originally wooded, which later became a formal garden facing the palace. With the demolition of the royal palaces and the movement of the royal family to the interior of Kew Gardens, the space, still Crown land, was used as an open space and later as a common for the residents.

The Green is largely unaltered in form since the first records of maps in the area. It is presumed that the triangle shape was produced by various factors, which can be observed in the map of John Roque from 1771, where the land was primarily allocated to the Prince and Princess of Wales's palaces. The gardens of the palace were bordered by Love Lane along the south end of the Green, and the River Thames to the north. Between Love Lane and the palace gardens was Kew Road, which was the main road connecting Richmond Palace to the area. As Kew Road turned toward the river, it cut off the distinct triangular section of land creating the form of the Green as it largely remains today. The presence of the Court at Richmond caused the courtiers to settle in Kew. Records of houses around the Green started to appear on maps in the 18th century. Furthermore, the Green was a connection between the village and Kew Palace, located in the west corner of the peninsula.

On the northeast side of the Conservation Area, the land had been referred to as the Ware Ground, with "ware" assumed to be a misspelling of "weir." This land was first given by Henry III to Merton Abbey, located in Merton, as fishing privileges for the religious community. On the west side of the land, the closest to the Green , was given to Sheen Charterhouse.

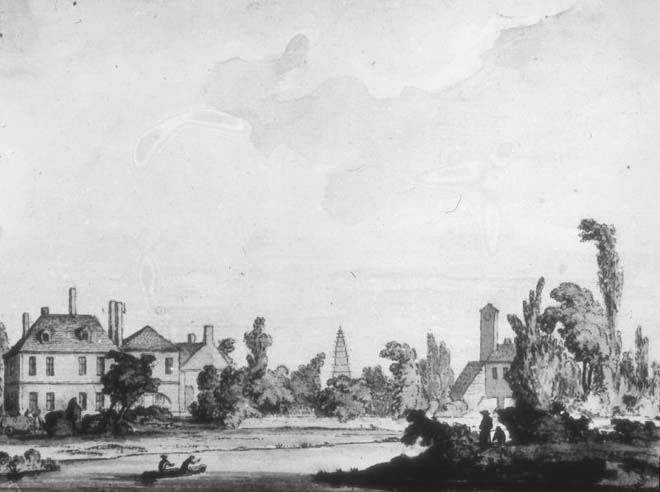

Figure 2: A view of Lord Bute's Erection at Kew, with some part of Kew Green and gardens (c.1767)

Figure 3: The Thames at Kew (1773)

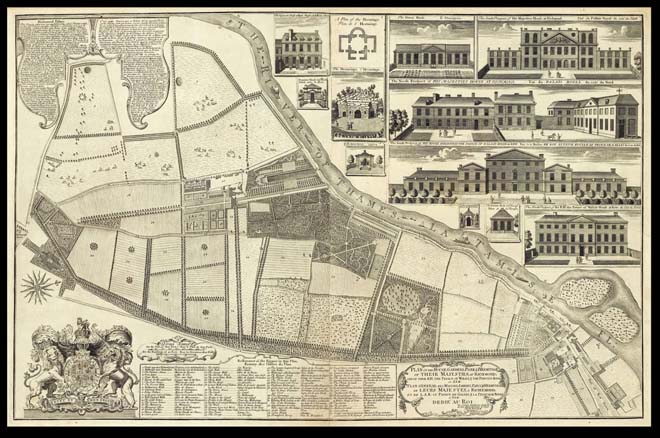

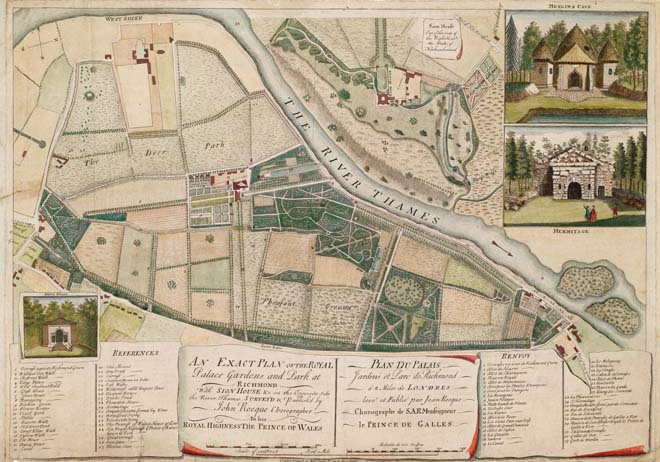

Figure 4: John Rocque's Map of Kew and Kew Gardens (c.1740)

During the mid-18th century there were eighty houses around the Green, and the cottages located around the Green were replaced by Georgian houses, attracting people of significance who had a relationship with the royal family.

Kew's population grew rapidly as the King's family resided there during the summer to escape from London. King George III and Queen Charlotte, together with their children, lived the longest in the palace.

In 1769, Kew was promoted from a curacy to a parish as the little chapel became too small, and the chapel was upgraded to a church. The King paid architect Joshua Kirby, the Royal Clerk of Works, to extend the building.

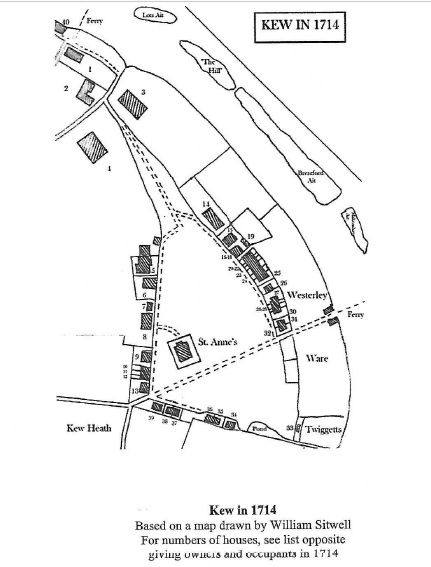

Figure 5. Kew Green in 1714, illustration from Queen’s Anne Little Church by David Bloomfield

Figure 6. Kew Chapel in 1714. Illustration from Queen Anne’s little church by David Bloomfield

Figure 7: John Rocque's Map of Kew Gardens and Park (1754)

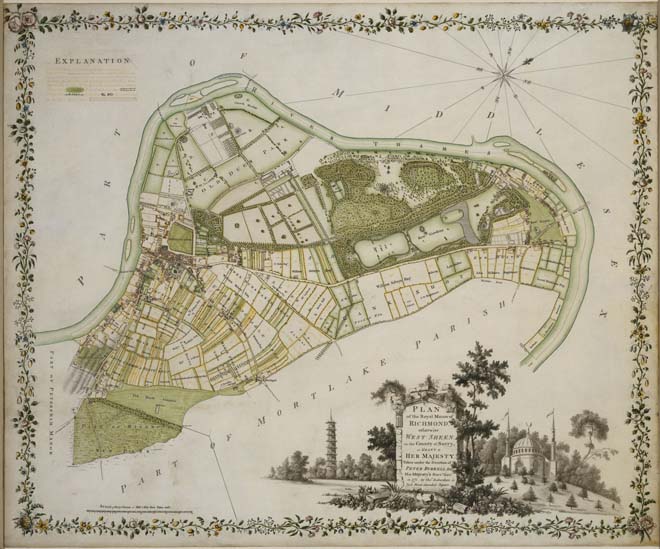

Figure 8: Plan of the Royal Manor of Richmond (1771). Kew is visible on the right

19th century onwards

In 1824, King George IV enclosed his estate with a fence, which ran across the Green on the line of Ferry Lane, with the intention of replacing the Dutch House at Kew with a new palace and to form a meadow east of the Green .

While the boundary was constructed, which separated the gardens from the Green, the remainder of his plan was never carried out.

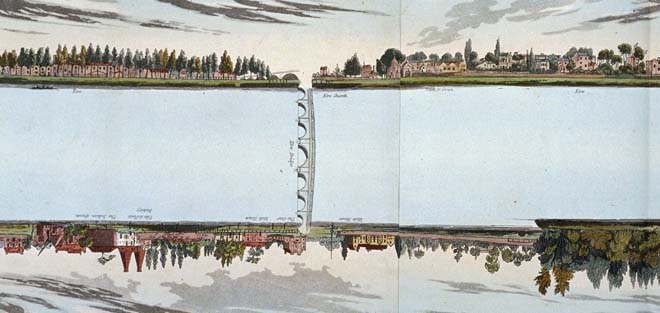

Figure 9: Extract from Samuel Leigh's 'Panorama of the Thames' (1829)

In the early 19th century Sir Richard Phillips described the Green as 'a triangular area of about 30 acres bounded by dwelling-houses’, and another description of a slightly later date speaks of the 'well-built houses and noble trees surrounding it. In the last century the Green was the scene of village sports, such as climbing the pole, jumping in sacks…’

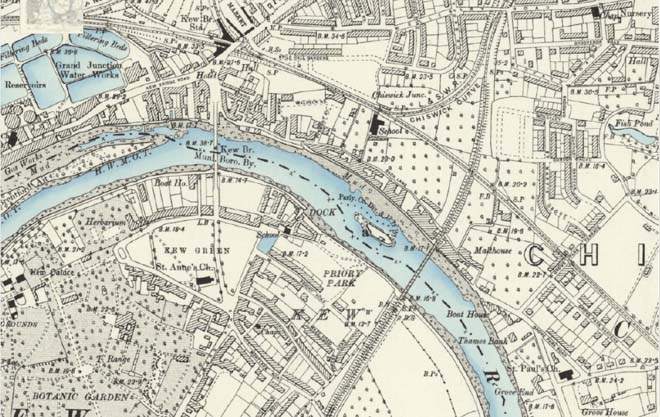

The railway arrived in Kew in 1869, connecting central London to Richmond. The new line was initially intended to run down towards the Temperate House, but the London and South Western Railway changed its mind and decided that Kew Gardens Station would instead be some 600 yards to the north, where it is still located. The village was altered by the railway's arrival, attracting more people to the area. Development followed to the east side of the Green, and tourists had easier access to the nearby Kew Garden.

At the same time, slightly larger houses were built all the way up Kew Gardens Road, which was linked to Mortlake Road by another two lines of houses bordering Cumberland Road. With the arrival of the railway, the area continued to transition from a rural settlement to a larger suburb of the surrounding area.

Figure 10: Map of Kew in the 1890s

With commuters in mind, new homes were constructed and in 1866, as part of the first stage of development, Forest, Maze, Gloucester and Priory Roads were under construction. The garden space in the houses and greenery provided by Kew Gardens was a feature that attracted people to move to Kew, allowing them to escape from the industrial environment of London.

Along the embankment, a distinct shift was taking place as the fishermen’s land was beginning to be converted into residential, with the creation of Westerly Ware’s Willow Cottages . Before this, there had been no substantial development here; some temporary buildings for the fishermen were in existence but mainly just meadows, trees, and rushes. The fishing industry had all but disappeared by 1850, as a result of pollution, but another customary riverside activity – harvesting osiers (willows) and rushes from the riverbank – endured for a few more years.

Towards the end of the 19th century, however, demand began to decline, and many who had been awarded riverbank land by the Enclosure Acts made the decision to sell their property in order for housebuilding. The developers first built Westerly Ware’s Willow Cottages in 1861, followed by Thetis Terrace in 1883. Then in 1886 and 1887 they first built Cambridge Cottages followed by Watcombe Cottages.

As the suburb grew and spread with development in the surrounding land, commercial uses started to increase. From the 1860s, many of the Georgian town houses were gradually turned to tea rooms, peaking in 1903. Mortlake Terrace, built at the same time as the Priory Estate, was constructed with the potential for future shops on the ground floor; later on, this became the first parade of shops in the area.

Figure 11: 'Bank Holiday, Kew' Camille Pissarro (1892)

During the Second World War, the Green was honeycombed with air-raid shelters, which offered safety during the Blitz. The Green, as well as Kew Gardens, was also used to cultivate vegetables for local residents.

As frequent in London during the war, railings were removed to assist the war effort. The only remaining iron railings that survive from that period can be found at the little triangle by the Elizabeth Gate, which remain in situ. Even though the area was bombed during the war, few buildings were damaged.

Westerly Ware stands on land that was used by 15th-century fishermen to pull up and dry their nets and sort their catch. The land was a water meadow used for cattle throughout the 19th century and then, in 1921, was landscaped and dedicated as a WW1 memorial, overseen by a committee of residents. Six clay tennis courts were laid out in 1926, with half replaced by a bowling green in the 1940s, following the arrival of Richmond Corporation as managers of the park. The playground was also created in the 1940s.

Development after the war was modest. The tea rooms along the Green eventually started to fall out of fashion and shut, a trend which was accelerated by with Kew Gardens offering the same services to visitors.

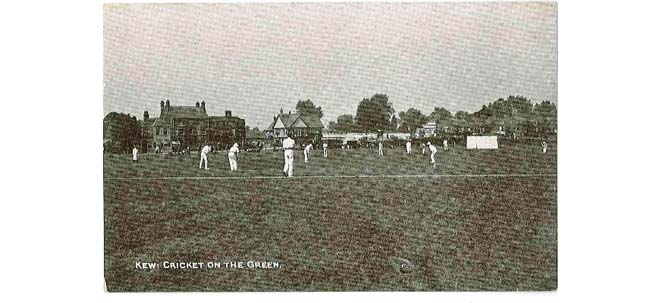

Figure 12: A game of cricket on the Green in 1903

Figure 13: Vegetables being cultivated on Kew Green in 1917

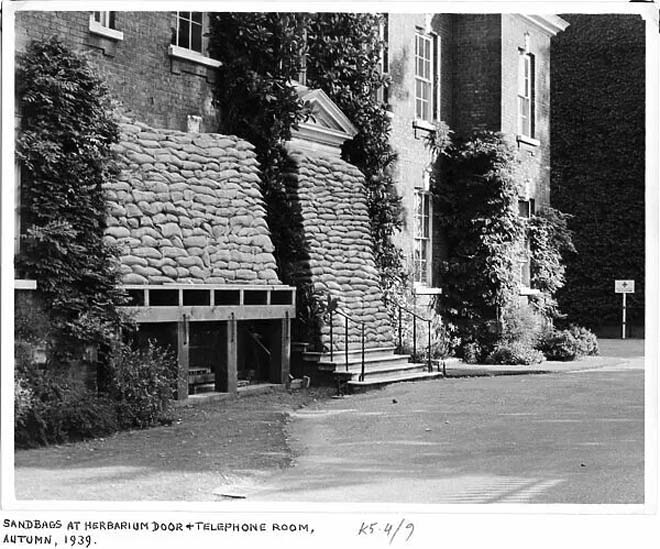

Figure 14: Sandbags piled up outside the door of Herbarium in 1939

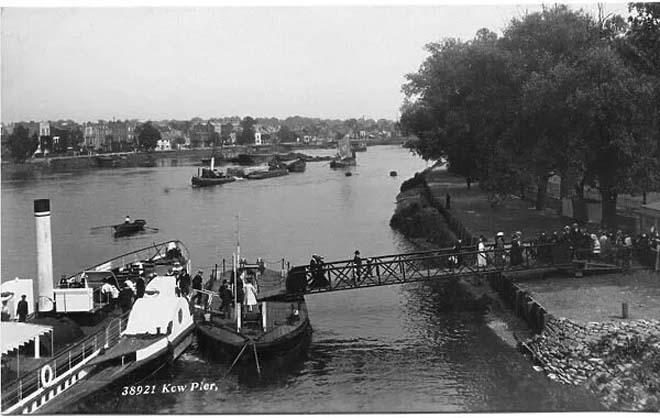

Figure 15: Kew Pier in the early 20th century

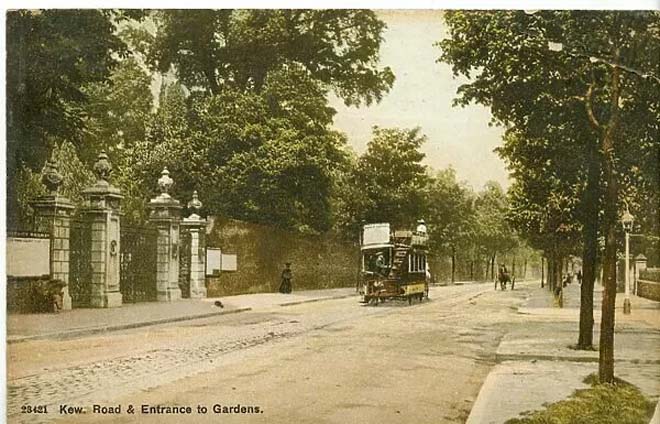

Figure 16: Kew Road and Victoria Gate in the early 20th century

Kew Palace and Gardens

Kew Palace, also known as the Dutch House, was built in 1631. The building was built on Sir Hugh Portman’s Estate, on the site of a Tudor mansion after the land was sold by Sir Hugh’s to Samuel Fortrey. Fortrey rebuilt the house in a Netherlandish style, in honour of his birth country. The house has been altered only slightly since its construction. Beneath the ground floor are remains of the older Tudor mansion, including the basement and foundations, which are the oldest structures that survive in the Conservation Area.

The relationship between Kew and Kew Gardens started earlier than the establishment of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. William Turner worked for the Duke of Somerset as a doctor in Syon House, on the other side of the River Thames. Turner acquired a residence in Kew, where he maintained a garden, the location of which is unknown. According to references in his book Herbal, the first edition of which was printed in 1551, he grew a formal garden with exotic species.

In 1717 Samuel Molyneux, a distinguished astronomer and Secretary to George II inherited the land where the Kew gardens are now located. After his death, Kew Palace was leased to Frederick, Prince of Wales. Prince Frederick, together with his wife Augusta, built a greenhouse, which signalled the beginning of Kew Gardens in its current form. In 1751, after the death of the prince, Princess Augusta was helped by John Stuard, 3rd Earl of Bute to develop the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew. Stuard was the honorary director of Kew Gardens and was later Prime Minister. He was also a resident of the area, owning No. 33 Kings Cottage.

Kew Gardens’ associations with royals continued until the last connection was severed in 1904, before which the royal family still used Kew Gardens and Kew Palace as their summer house. After the death of the Duke of Cambridge, Kew Gardens were transferred from the Crown to the government and subsequently opened to the public.

Kew Pond

Kew Pond dates to before the Norman Conquest. Originally, it was a natural pond fed from a creek on the tidal River Thames and was enlarged in the 10th century to serve as a fishery. The pond was first mentioned in 966 by the Saxon King Ethelred in a grant made to the Church of St Peter and St Paul in Winchester, and it is described as “a fishery at Kaio juxta Braynford”. It is also frequently mentioned in historical accounts and charters from the 11th and 12th centuries.

During the 18th century, it was not uncommon for the pond to be used for domestic activities such as watering livestock and cleaning carriages and cartwheels. The pond is clearly shown in the 1771 Manor Survey of Richmond map. To provide access to the King's School, which was constructed to the north of the pond in 1824, the stream which connected the pond to the River Thames was partially filled in and covered over. A concrete ramp and walls were constructed in the early 1890s, to address accessibility issues to the school.

The pond, as shown on historic maps, did not have any permanent buildings around it until 1873. In 1894, Priory Road was built, presenting for the first time buildings on the southeast side, but the buildings did not respect the pond itself. This changed with further development of the area, when houses were constructed on its east side, with the creation of Bushwood Road a few years later.

In 1934–1935, the pond was infilled with concrete and railings were built around. It was subsequently used as a parking lot, a playground, and through the 1950s, it was frequently the site of tipped rubbish. Following extensive talks with the Council, the Friends of Kew Pond were established in 2010, and a management plan for the refilling and restoration process were agreed. Today, the pond provides a habitat for a variety of wildlife and contributes to the biodiversity of the area.

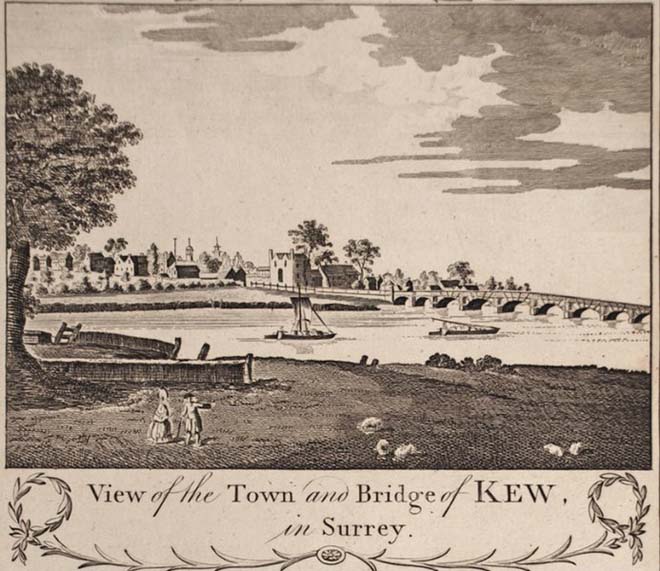

Kew Bridge

Until the middle of the 18th century, there was no bridge across the River Thames from Kew to Brentford. The first bridge, a wooden structure built by John Barnard, was constructed in 1758-59. As the wooden bridge was damaged by a boat in 1774, during 1780 it was replaced by a stone bridge designed by James Paine. A toll was charged on this bridge until the Corporation of London and the Metropolitan Board of Works purchased it in 1873, becoming a free bridge as part of a campaign to make free from toll the five bridges of Kew, Kingston, Hampton Court, Walton, and Staines. The bridge was closed to traffic in 1899, and a temporary one was erected during the construction of the present bridge, which was opened in 1903.

This new connection created an easier way to travel to central London, attracting more people to move to the area.

Figure 17: Illustration of Kew Bridge (1774)

Kew Railway Bridge

The bridge was built in 1869 by the London and South Western Railway Company, extending the line from South Acton Junction to Richmond.

The bridge was designed by W R Galbraith and built by Brassey & Ogilvie. It is 575 feet long and has five wrought-iron lattice-girder spans supported on cast-iron columns with ornate capitals, which carry two railway tracks across the river.

Figure 18: Kew Railway Bridge in 1870

Part 2: Conservation Area Appraisal

Location and Boundary

Kew Green Conservation Area is located south of the River Thames. It is bounded by Kew Road to the south, the river to the north and west and the railway line to the east. It adjoins Royal Botanic Gardens Conservation Area (no.64) and Kew Road Conservation Area (no.55) to the south and Kew Gardens Kew (no.63) to the southeast.

Setting and Topography

Kew Green Conservation Area is formed around the Green as an open space visible from any viewpoint. The Conservation Area is under the buffer zone of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew World Heritage Site.

The Green is surrounded by prominent buildings facing the open space, and in the west corner St. Anne’s Church leads the view as you get closer to the area from the south. The noisy road of the A205 crosses the Green from south to north, following an existing division of the Green.

The open view across the Green and proximity to the River make it exceptionally sensitive to tall developments within its setting which could harm the ability to appreciate its domestic scale and semi-rural character.

The topography of the Conservation Area is relatively flat, with no significant inclines. Due to the construction of Kew Bridge, the approach roads were raised and the streets around the bridge are at a lower level giving a sense of drama to the streetscape.

Figure 19: Aerial view of Kew

Open Spaces and Trees

The Green

The Green is the primary area of public open space and the oldest unaltered layout within the Conservation Area. There are a variety of green spaces, predominately the riverside of the Thames and Kew Pond, which contribute positively to the rural landscape of the area.

The Green is a triangular open space of 30 acres. The existence of the open space dates from the 17th century and the layout has not been altered since this time. The open space is bordered by mature trees. The centre is divided by the A205, creating an impression of two spaces. The east side of the Green is plain, with mature trees surrounding and two paths that cross the space in parallel. Kew Pond faces this area of the Green, reinforcing the suburban character of the area.

On the larger west side, two buildings were added to the space, St Anne’s Parish Church in the southeast corner and a sports pavilion in the northeast corner. Trees are mainly located on the riverside and around the Green, functioning as a natural boundary, but there also street trees within the residential area. Front gardens make a positive contribution to the landscape setting of houses and add to the leafy suburban character of the Conservation Area. Consistent well planted front gardens unify the Priory Estate streets and soften its overall appearance.

The Green, St Anne’s Churchyard and Kew Pond are on the London Gardens Trust Inventory.

Fiugure 20: Kew Green

Figure 21: Kew Pond

Figure 22: Westerly Ware open space

Thames Riverside

The riverside of the Thames is a natural boundary for Kew. The Thames Path passes through the area from Kew Railway Bridge to Kew Garden. T he River Thames and the allotments on the south side are experienced in a pleasant walk. Small cottages that face the river start to introduce a domestic element to the area.

The path is not paved, with trees on both sides, and narrow with a short boundary wall. Remnants of historic infrastructure can be observed, such as the old pier next to the new one, providing a riverside feeling. The path continues until Kew Gardens, opposite Brentford Ait. Westerly Ware, which is located between the Thames Path and Thetis Terrace, contributes to the openness of green space with a valuable garden with trees, bushes, and a small orchard on the east side.

Figure 23: Thames Path

Brentford Ait

Brentford Ait is a long 4.572-acre uninhabited ait which has a gap in the middle known as Hog Hole. The ait has borne large trees since the 1920s, originally planted to screen the now demolished Brentford's gasworks. The ait is covered by willows and alder and is also a bird sanctuary.

These riverside areas form an important part of the 'Arcadian Landscape' of visually interlinked landscapes of historic importance associated with the River Thamess. More background can be seen in the Thames Landscape Strategy.

Figure 24: Brentford Ait from Kew riverside

Short Lots

Short Lots are allotments on the northwest side of the Conservation Area and contribute to the landscape of the riverside, reinforcing the suburban character of the area.

Figure 25: Short Lots allotments

The Royal Botanic Gardens

The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew are not visible due to the high boundary walls which enclose the gardens in most of the Conservation Area. Only a small section is within the Conservation Area, although that still has a strong domination in the landscape on the west side of the Green. The Elizabeth Gate welcomes visitors with a peek into the massive open space of the gardens with tall and mature trees acting as a natural boundary that divides the two Conservation Areas.

The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew World Heritage Site was designated in July 2003, 20 years after the designation of the Conservation Area. Some parts of the World Heritage Site as well as the Buffer Zone are within the Conservation Area. Some of the buildings on the south side of Kew Green, which back directly onto the gardens, and Cambridge Cottages have direct access to Kew Gardens. The whole site is Grade I on the Historic England Register of Park s and Gardens of Special Historic Interest.

Townscape Overview

The layout, and thus the appearance and experience of the Conservation Area, is dominated by the Green, a triangular area of about thirty acres which is visible from all character areas. The tree lined avenue of Kew Road bisects Kew Green towards Kew Bridge.

Outside the Green, the area is predominantly residential with buildings that are typically two or three storeys and semidetached or terraced. There are only a small number of shopfronts to the ground floors of otherwise residential Georgian houses.

The area developed principally due to its proximity to Kew Palace (and previously Richmond Palace/Sheen Manor), providing architectural interest reflecting its connection with the Court and fashion, and a cohesive townscape. The area's rural character remains, including footpaths and cottages on the riverside.

The approach over the River Thames is of an unfolding townscape with views east and west of the bridge. The layout of the area developed around the Green and later extended to the east, and this is reflected in the building types. With few exceptions, later changes to townscape have primarily occurred along the riverside, but these changes are largely sympathetic in their design and scale and have allowed for the retention of much of the historic fabric in the area – which is within the area also being within the buffer zone of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew World Heritage Site.

The paving used in the Conservation Area is very cohesive and uniform, with high-quality York stone pavers with granite kerbs. On Cambridge Road a good surviving example of granite setts can be observed, which reflects the rich history of that specific settlement.

Spatial Analysis Overview

The spatial composition of the Conservation Area is focused on the intrinsic relationship between the triangular public space with its surrounding historic buildings, including the entrance to Kew Gardens. The open space of Kew Green offers panoramic views of the area, with St. Anne’s Church located in the southwest corner forming a focal point with its octagonal clock tower.

Kew Road with its avenue of trees bisects the Green, and the arrival at Kew Bridge is marked by a parapet with historic lampposts.

Kew Road functions as the South Circular Road (A205) and is dominated by traffic, which has a significant influence on how the area is felt and seen. Traffic disjunction, both physically and visually, has a detrimental effect on the quality of the urban fabric and public realm. The road has wider pavements, and a greater diversity of buildings is located along the south section, leading into the Conservation Area. The spaces between the Victorian mansions in the south differ from the unified row of terraced buildings in the north, a marked change compared to the densely developed Priory Estate to the east. Larger houses around the Green are generally set within significant plots and set back from the road, although a few are fronting Kew Road. Despite a consistent building line, many houses have variation in depth, employing bays and other projecting elements, which adds visual interest and avoids the impression of a singular mass or terrace. Variations in roof type and height also contribute to this difference.

Smaller houses can be found in reasonably sized plots throughout the whole area but predominantly in the riverside area. Within the Priory Estate, the streets are all quite narrow, which contributes to a more suburban character, and traffic is more noticeably absent.

A mix of semi-detached houses and terraces adds variation to the streetscape but front gardens and spaces between houses add a sense of greenery.

The Conservation Area is set in a curve of the River Thames, and this greatly impacts how it is experienced and perceived, particularly within the riverside character area. The curve results in sweeping and changing views, primarily out of the Conservation Area, given the greenery and slight elevation that occurs to the south.

Street Furniture Overview

Lamp columns are generally consistent in the area; black Victorian inspired posts with modern lighting within glass lanterns. There are a group of rare early 19th-century cast-iron gas lamps to the west of the Green near the entrance to Kew Gardens, all of which are Grade II listed . There are a small number of surviving Victorian sewer vents that are made from cast iron around the Green, whereby the best example located close to the entrance to the Gardens is Grade II listed. The columns have the maker’s name inscribed - F. Bird & Co., 11 Gt. Castle St. Regent St.

At the entrance of Kew Gardens, near Elizabeth gates, is a K6 Telephone Kiosk, the only one preserved in the area.

In terms of public realm furniture, wooden benches are located around the Green and Westerley Ware, being consistent in design; a few of them are memorial benches.

Around the riverside, there is the new pier, used mainly during the summer to connect Kew with central London. The area around the pier is furnished with benches and there is a public sculpture of a keyhole by Mark Folds, a reference to the Anglo-Saxon name for Kew “cayho”.

Figure 26: Victorian sewer vent pipe

There are some historic letterboxes, and one ‘wall box’ located throughout the conservation area. The wall box is mounted on the boundary wall of no.45 Kew Green and dates from George VI’s reign. A Victorian letterbox survives in Priory Road.

Figure 27: George VI 'wall box'

Figure 27: George VI Letterbox

Figure 27: Victoria Letterbox

Architecture Overview

Buildings are predominantly Victorian on the east side within the Priory Estate, with Georgian houses around the Green, due to its proximity to the royal palace. Cottages are located throughout the area and are reminiscent of its former rural character. However, the majority, which are located along the riverside, are from the mid-19th century, as a later extension of the village. Contemporary housing is not common in the area, although a few modern developments to the riverside have been introduced incorporating sympathetic designs and layouts.

The scale of buildings is cohesive, typically semi-detached, or terraced houses of two or three storeys. The area has various distinct architectural styles in different character areas, depending on their period of development.

Most of the buildings in the Conservation Area are designated as either statutorily Listed Buildings or Locally Listed Buildings (Buildings of Townscape Merit). There are 38 listed buildings, 223 Buildings of Townscape Merit, two Grade II listed bridges and the buffer zone of Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew World Heritage Site.

Shops are located mainly on the corner of Kew Road and Mortlake Road, with good examples of surviving historic shopfronts.

The evolutionary character of Kew Green, shifting to reflect the transition from palace to more suburban development , results in clear stages of urban development and variations in their overall character. While this document identifies sub-areas that have a more obvious and legible shared character and appearance, this section will broadly outline common styles, materials, and features, which are evident and relatively consistent throughout the Conservation Area. The descriptions are not exhaustive, and where clear variations exist; these are addressed within the appropriate character area descriptions.

Architectural Details

Windows

Painted timber sash windows are the most common window type with few exceptions. This consistency of window form and materiality forms a significant feature of the Conservation Area, providing unity of appearance to the buildings , and contributes to the strong historic character of the area. Whilst there is a consistency in window types, there are subtle differences in the number and size of the panes and the thickness of the glazing, which reflects the age of the building. Georgian sash windows are characterised by 6 panes over 6 panes. In contrast, Victorian windows predominately have two over two-panel grid designs.

Figure 28: Detail of a window in Kew Road

Figure 29: Detail of a sash window

Brickwork

The most common material in the area is brick. Stock brick in yellow, cream, and shades of red are all common, particularly in the Priory Estate character area. Typically, buildings finished in Flemish bond are characteristic of the area.

Figure 30: Detail of brickwork in Kew Green

Porches

The porches in the area consist predominantly of two styles: neo-classical pedimented porches for Georgian houses, and gabled pitched timber roof porches for 19th and 20th century houses and cottages. The roof finishes of the porches match the finishes of the houses.

Figure 31: Pitched roof porch

Figure 32: Modern well designed porch in Bushwood Road

Figure 33: Gabld porch in Kew Road

Figure 34: Brick entrance porch with stone surround

Figure 35: Classical style door surrounds in Priory Road

Cast-iron features

Cast iron railings are common in the area and are found in 18th and 19th-century houses.

The predominant railing in the area is simple iron with notable ornamental finishes. The Georgian houses mostly have railings in a simple design with square or round railing bars topped with spiked heads. A few of these Georgian houses present Edwardian railings, with plain round railing bars with decorative heads.

Victorian railings are more present in the Priory Estate, although still not very common, and contain elements such as twisted railing bars, rosettes, and a variety of finial types.

Wrought iron is used to decorate balustrades and railings to windows, as well as for rainwater goods like downpipes and gutters. The balconies with detailed balustrades in diverse colours decorate the front facades of several houses facing the Green. Delicate balconies of wrought or cast-iron with curving metal or clay roofs resembling Chinese pagodas are also found in the area.

Figure 36: Windows with metal guards

Figure 37: Blue iron railing balcony in Kew Green

Figure 38: Iron balcony railing

Front Boundaries

Boundary treatments are common given the prominence of gardens and generous plot sizes to the area, and there is variety to their treatment respondent to building type and period. Brick boundary walls and iron railings with gates are common, and their appearance is often mitigated by bushes, hedges, trees and ivy which add a green setting and enhance the character of the area. Generally, boundary treatments are low brick walls in the Priory Estate, occasionally with rails above, and timber fences with low gates in the riverside. Within the Green, walls are taller, reflective of earlier building styles and conceal more formal front gardens.

Overall, boundaries are consistently low in the conservation area. Front gardens, glimpsed views between houses, and mature planting help break up the street scene and contribute to the overall green character.

Figure 39: Front gardens and white picket fences in Thetis Terrace

Shopfronts

Nos. 1 to 9 Mortlake Terrace is an excellent group of traditional shopfronts, preserving most of the typical features of a traditional shopfront, including console corbels, a largely unaltered fascia, transom, and stall riser.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Kew Green had many tea rooms, which were created through the conversion and sometimes expansion of ground floor of existing houses. These had largely fallen out of fashion in the 20th century, after which the ground floor was reintegrated as part of the residential building. Most of them used the back gardens as terraces during the summer, facing the River Thames or Kew Gardens. This is particularly evident at Nos.15,27, and 63 where the historic shopfront survives within a residential dwelling.

Overall, the quality of shopfronts is good, with many traditional details surviving and later alterations being sympathetic in appearance, scale, and materials. Details of a few examples of high-quality shopfronts are described below:

The Cricketers is a public house, formerly known as the Rose & Crown , two storeys with deep part hipped part gable roof, with a painted brick finish on the first floor with exposed timber framing in Tudor revival style. Timber casement windows with lead lattice reinforce its medieval style.

The Greyhound public house is a revival Tudor building with exposed timber framing on the first floor and a very detailed shopfront on the ground floor. The shopfront presents a bow window decorated with iron columns and stained glass above, presided over by a classical pediment in the middle of the window.

Nos. 10 to 16 Kew Green are a surviving group of shopfronts which preserves, with some alterations, a traditional shopfront with glazing divided into small panes and fanlights over the doors. No. 14 is the only one heavily altered but still preserves the timber shopfront painted in electric blue.

Figure 40: Shopfronts in Mortlake Terrace

Street Name Plates

A few streets in the area have retained ceramic tiled street name plates, reinforcing the rural character of the area.

Figure 41: Example of a ceramic tile name plate

Character Areas

Despite the cohesiveness of the area, there are four legible sub-areas which have shared development history, but each retain a distinct character.

- Kew Road

- The Green

- Riverside

- Priory Estate

Character Area 1: Kew Road

Summary

The area is focused on the southern section of Kew Road, south of the junction with Mortlake Road, which forms an important approach into the Conservation Area and to Kew Green. The west side of the appraoch is characterised by the tall brick boundary wall which surrounds the Botanic Gardens, and includes Victoria Gate, Avenue Gate, and Lion Gate. On the east side, a high boundary wall and mature vegetation is punctuated by a number of gateways and houses dating from the 18th and 19th centuries, many of them listed. Many of the houses form short terraces or pairs.

Although the Green itself is not visible from this part of Kew Road, the architectural style is consistent with the Green and the houses at the north form part of its setting. The group of listed 18th-century houses at the north end is most important in Green's setting, as they were built during the same time by the frequent visitors of the palace.

The architectural style is consistent with houses built around the Green, with many buildings dating from the same period, and were constructed along the historic route which lead to the royal palaces, and thus had a status associated with their location. Houses closer to the Green are slightly older and more robust, where houses to the south reduce in scale and there is a higher proportion of Victorian infill.

The area is primarily residential, with the busy road as a central axis that connects the southern side with the Green.

Figure 42: Victorian houses in Kew Road

Townscape Overview

Kew Road has always been closely associated with the royal palace, first with Richmond Palace and later with Kew Palace, serving as a route between them and London via ferry across the River Thames and later via the bridge. The Kew character area forms the southern entrance to the Conservation Area and the first approach to Kew from Richmond.

As one travels into the area via this route, the boundary walls of Kew Gardens, on the western side of the road and ending at the junction of Kew Road with Mortlake Road, guide the visitor around the Gardens and towards the Green. The wall also serves as an obvious point of reference, demarcating the boundary between Kew Gardens, Kew Conservation Area, and Kew Green Conservation Area. The presence of taller trees visible beyond the wall hint at the presence of the Kew Gardens behind the wall.

At the end of the road, there is a junction with Mortlake Road and Kew Green Road. On the west side, at the end of the boundary wall, the remaining structure of the former old Kew fire station is visible, inserted in the boundary wall itself, with three segmental arches and central window still visible.

Figure 43: Old Kew fire station

A variety of architectural styles are apparent on the eastern side of Kew Road, predominantly Georgian closer to the Green and Victorian to the south, reflective of the development of the road alongside its former relationship with the royal palaces which attracted the nobility to the area who, in turn, constructed large villas on the Green. The road itself was widened in the 1930s to accommodate increased traffic through the area, with the increase in popularity and accessibility to cars.

The eastern side begins with a group of detached Victorian villas of three storeys with gabled roofs set back from the road, a positive feature as their grand scale contributes to an avenue character of the road leading towards the Green. The spaces between the houses and their impressive entrances are a defining feature of this part of the Conservation Area and they contribute to a sense of openness. The villas continue a character and scale which begins in the adjacent Kew Road Conservation Area but have a more legible development history associated with the Green itself.

Passing Kew Gardens Road, the buildings become smaller in scale with a cohesive low roofscape. Georgian houses and cottages coexist, with a clear transition north of the road to two storeys with small front gardens introducing the rural character of Kew. Decorative porches and iron balconies are a predominant feature. A short cul-de-sac, James’s Cottages, leads away from the main road, and houses a group of six terraced houses. This short street is the only remaining aspect of the rural English village street pattern surviving in this character area.

Continuing north are a group of 18th century houses, in brick or stucco; No. 352 is the most distinctive with an excellent Adam style doorcase.

Buildings

This street comprises a mixture of housing types, including detached, semi-detached and cottages, ranging from 2-4 storeys in height. They also contain a mixture of single-family homes, and slightly larger blocks containing flats. Nos. 266-280 are a group of houses similar to those within Kew Road Conservation Area, located between Broomfield Road and Kew Gardens, at the south end of the Conservation Area.

These houses are built in yellow and red brick, with timber sash windows and natural slate roofs with clay crested ridge tiles and are four storeys with a gable front to projecting bay. Nos. 266 to 274 differ from the other group of houses in terms of the brick colour, instead finished only in yellow. Another architectural feature that contrasts from one group to another are the main entrances; the first group has a classical portico, and the latter has a characteristic gabled porch with clay tiled roof.

Figure 44: 276 Kew Road showing a gabled porch and gabled roofs

The Original Maids of Honour Public House is the only commercial building within this character area, which is otherwise entirely residential. The building is two storeys, with exposed red brick in the shopfront and white rendered on the rest. The shopfront, on the projecting bay elements, has a charming round window with glazing divided into small panes. A traditional clay roof porch surrounds the windows, with a recessed front entrance. The original iron cast downpipe is still preserved in the front elevation. Its unique character positively contributes to the appearance of the street as it retains many of its 19th century features.

Figure 45: The Original Maids of Honour

Figure 46: 250 Kew Road

To the north towards Mortlake Road, this area is distinguished by cottages of 1-2 storeys, creating a varied roofscape as taller buildings are inserted between smaller ones. There is little variety of building materials, but brown brick is predominant, and a few cottages have a rendered façade. The front gardens from No. 294 to 316 are uniform, establishing an even perpendicular line of boundary walls. The houses were built facing Kew Gardens.

Previously the gardens didn’t have any physical boundaries, which was a key point for the placement of those houses around a main road that connected two royal palaces and allowing views to an open space. Nowadays a tall brick boundary wall makes a separation and prevents the views to the gardens from Kew Road.

The cottages located between Nos. 296 to 322 are two storeys high, with rendered façades and front gardens with timber or railing gates to brick boundaries.

Further north, there is an opening between No. 322 to 336, previously the entrance to Gloucester House, used by George’s III brother: Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh. The open space creates a visual division between Kew Road, and the appearance of the area transitions to the formality and scale of Kew Green.

James’s Cottages are located in a cul-de-sac between Nos. 342 to 344. The group of houses beyond is an exceptional remnant of the former past village character of the area, but they are not visible from the street.

No. 294 is a late 18th century symmetrical double-fronted two-storey house with a central elliptical arched doorway flanked by two-storey segmental bays. The front porches are different, adding variety and interest to the group. Within this group, No. 318 has a characteristic terraced balcony with white railings, which imitates the balconies facing Kew Green. Nos. 338 to 342 are three early 18th-century cottages of two storeys with roof dormers. The group have a distinguished stucco band on the first floor and brown brick with red dressings on the façade.

The group of houses closer to the Green, from No.344 to 356 can be read as a group of Georgian houses which range between two and three storeys. No. 352, formerly known as Heathfield House, is a late 18th-century house with a prominent white rendered façade built by the Engleheart family. It has three storeys with projecting bays to the main elevation, an excellent doorcase with slender debased Ionic pilasters, a frieze with figure brackets, a central embellished panel and a blind fanlight with plasterwork fan above plaster Leda and the Swan figures.

Overall, the mixed brick facades with No. 350 rendered illustrate the key historic development phases of the area, with the austere Georgian buildings illustrating the connection with Kew Palace. Houses are generally designed as detached, set back from the pavement behind small front gardens. No.356, an end corner detached house, has a later rendered extension facing Mortlake Road.

Figure 47: James Cottages

Character Area 2: The Green

Summary Description

This character area focuses on the Green itself and includes all the buildings that surround it, the residential streets to the east of the Green, as well as the northern section of Kew Road. The Green is the heart of the Conservation Area, whereby the western part of this character area focuses on the church and the eastern part focuses on the pond. The Green contains the oldest buildings in the Conservation Area as well as local shops, formed of small clusters, particularly along Kew Road. The buildings which surround the Green represent a variety of periods and architectural styles, all of which are of high quality in terms of architectural treatment and character and represent a key element of the area’s significance. The Green both serves as an important historic open space, central to the Conservation Area but also as an important recreational space for the public, including its use as a cricket pitch during the summer months, an activity which has taken place on the Green since the 18th century.

The western side of the Green generally has a greater concentration of larger, grander houses than the east due its proximity to the former palaces and Kew Gardens. The eastern side however has greater variety in architecture with a mix of cottages, mansion blocks and terraces, which provides a more enclosed feel. This part of the character area also retains some commercial focus with Mortlake Terrace, an attractive parade of shops whose upper floors are unaltered, as well the Coach and Horses Public House.

Although the A205 divides the Green, the impact of the traffic is partly mitigated by planting, with mature trees adding greatly to the leafy suburban appearance of the area.

Townscape Overview

The area is dominated by the open space of the Green which has largely remained unaltered in its form since its creation. The one exception is the division of the Green by the A205, which results in the visual subdivision of the space into two. The avenue of trees also serves to visually divide the space. Development on the Green itself has been avoided except for Saint Anne's Parish Church, the War Memorial and the cricket club, which are located on the southern corner. Accordingly, the layout of the area remains largely as it was when the Green was laid out.

The western part of the sub area surrounding the Green has a grander scale with large semi-detached and detached houses of two and four storeys, many of which are set back behind high walls or well landscaped front gardens. The building plots are also generally larger, increasing the sense of scale. The eastern section is more enclosed, with most of the house being of smaller scale, generally of two to three stories and in rows of terraces. Many of the houses are also situated close to the pavement edge or with smaller front gardens, emphasising this more enclosed and intimate feel. The area, however, starts to open up around the pond where some larger buildings address this space.

There is a distinct variety in age and architecture of the buildings within this sub area, although there is a particularly high concentration of 18th century buildings, built when the court settled in Kew Palace for longer stays. Despite the similar construction date, there is some variation in design or style, adding to the variety and richness of the area and illustrating the changing fashions in architectural design.

Red and stock brick are the principal materials within the character area, which provides a consistency to the streetscape, although some buildings retain rendered facades, particularly on the southern side of the Green. Modern buildings have been inserted successfully within the sub area, maintaining the consistent heights, scale and use of brick, all of which form important elements of the character of the area.

Kew Green West Side

The built architecture of Kew Green can be separated into different sections, due to the triangular shape of the Green, as well as Kew Pond, which act as natural dividers.

The western part of the Green is lined with notable historic houses, mostly Georgian, framing the entrance to the Kew Gardens at its western extent. The buildings on the south side of the Green, between the garden entrance and the junction of Kew Road form an important collection of buildings, many of which are listed, date from the 18th century and have an important relationship with Kew Palace and Kew Gardens. Many of these buildings remain part of Kew Gardens, maintaining an important historic connection with the royal park.

The curved façade of Mortlake terraces receives visitors to the south side of the Green, highlighted by St. Anne’s Church in the west corner.

On the easterly side, the scale is smaller, and the buildings are more modest. Remnants of former shopfronts can be observed in No 15, now in residential use. The buildings step back from the road with small front gardens. This includes Nos. 17-25 (even) which form a group of largely three-storey Georgian buildings, with cohesive frontages and many surviving historic features including sash windows and door surrounds. The scale of height increases through the west side, decreasing with No. 27. This rendered house of three storeys has a traditional shopfront now converted into residential on the left side and a small front garden on the right side. Nos. 27 to 31 create a separation in the largely consistent brick architecture; they are three stories with attic levels and basements and stuccoed. This pair are also set further back from the established building line further east with landscaped front gardens. Besides, No.31 acts as a natural partition between residential Kew to the east side, historically related to the royal botanic gardens. A single-storey brick-built double garage separates No.31 from No.33, adjoining a visual gap in the townscape and alteration in scale. This seeks to increase the assertiveness of no. 33, the residence of the Earl of Bute, a prominent three-storey building set close to the pavement edge with a small front lightwell. This building next to it was used as the Earl of Bute’s study, the study acts as a division between buildings that still have access to Kew Gardens and those where is lost.

The next building, No. 37, known as Cambridge Cottage, also known as Kew Gardens Gallery, is a long house approached by a magnificent Greek Doric portico, which projects into the street and thus breaks the building line, forming a prominent feature along this part of the Green. The portico was used to protect the visitors to the palace from inclement weather on the arrivals by carriage. The structure still preserves the step to help people to get down the carriages. Nos. 39-45 (even), the Gables, is a group of later construction with a courtyard fronted with a magnificant white mulberry tree. The boundary wall still preserves the original cast and wrought-iron gates.

From No.47, the houses are set back behind a tall boundary wall, and few glimpses are visible from the Green. No. 47, known as the Admin Building, was the original entrance to the gardens adjacent. A plaque on the right of the gate marks the former main entrance to the gardens.

Nos.49 to 55 buildings are diagonally positioned to the Green and face the Gardens, having a strong relationship with the Gardens, which continues as most of these buildings are used as Kew Royal Botanic Gardens headquarters.

In the Elizabeth Gate corner, a small cul-de-sac with two-storey cottages are facing No.51 instead of the Green. No. 55, known as Herbarium House, is a two-storey brown brick house with a central doorway with a Corinthian doorcase, set at the end of the houses on the southwest side of the Green.

The Elizabeth Gate is flanked by single pedestrian gates hung from smaller stone piers. The gate is the principal entrance to Kew Gardens, is set back and separated from the Green by a roundabout, used to collect visitors by buses or private transport. This grassed circular element or roundabout creates a visual separation between the Gardens and the Green.

Between Ferry Lane and Elizabeth Gate is the Herbarium complex, which comprises seven buildings, which together form two informal quadrangles. The building façade fronting on to the Green is Hunter House, which is a seven-bay Georgian building of three storeys, set behind tall black iron railings and with projecting corner bays, a doorway with Ionic columns and pediment, and windows with feathery keystones. The Herbarium is the largest building in the Conservation Area and is set back behind brick boundary walls closer to the Elizabeth Gate. It has a four-storey modern addition to the back that faces the riverside. Hunter House, a former residential dwelling converted in the late 18th century to house the Herbarium collection, contributes positively to the streetscape on the north side of the Green, as it presents similarities in scale and material to the buildings located in the north of the Green. The pavement in this section, which footpath only in one side, is completely distinct to the other areas of the Green, with pavement flanked by London Plane trees.

Figure 48: View of the southern side of the Green from the War Memorial

Figure 49: Cambridge Cottage

Figure 50: Cambridge Cottage porch with view across the Green

Figure 51: Rear elevation of Cambridge cottage

The northeast side of the Green has back gardens facing the riverside. Ferry Lane, created as part of the formation of boundaries in the Herbarium during the reign of George III, is a narrow space, linking the Green to the Riverside. The sense of enclosure is achieved through the boundary brick walls of the Herbarium and 59 Kew Green as well as the lack of street pedestrian pavement.

Tall mature trees also line the tree on the east side, providing a semi-rural character to the lane which contrasts with the formal and open space of the Green. At the end of Ferry Lane is Kew Green Preparatory School, a grand plum and red brick building of three storeys, which maintains the Georgian proportions of the prevailing architecture despite being a later building. Past the school, there is the path along the River Thames, and to the north side is the boundary wall of Kew Gardens. The road goes towards the west, lined by the boundaries of Kew Gardens on one side, and the River Thames on the other side, until one arrives at an open space used as car parking for Kew Gardens.

The buildings to the east of Ferry Lane towards Bush Road largely share a uniform brick façade and consistent scale, being three and four storeys in height. Most are listed and have 18th century origins. The houses on this side of the Green generally have deeper front gardens and the boundary walls are lower, allowing the buildings to appear more assertive and grander in the street scene. The projecting bays and porches prevent the group from appearing overly flat despite all following the same building line. Furthermore, many feature elaborate first floor iron balconies, which accentuate the importance of these upper levels and add visual interest and variety to the streetscape. Front parapets are the most co mmon feature of the roofscape of this group although there are mansard storeys and surviving M-shaped roofs which result in an interesting roofscape.

The variety of tall chimney stacks also forms an important feature to this part of the Conservation Area, particularly with views from the southern part of the Green where the varied roofscape is best appreciated with little development breaking the roofline. Most of the buildings are brick but there are some which are rendered, including no. 67, which has a vibrant blue balcony that provides colour and visual variety to the street scene.

Figure 52: Ferry Lane

The Cricketers Public House is a detached two storey building with a timber exposed frame on the first floor, which contrasts with the cohesive classical style of the group of Georgian houses further to the west. The pavilion, which slopes away from the level of Kew Road and faces the Green, has a small seating area that differs from the character of the Green, where the seating spaces are located within the boundaries without interfering with the open space.

Figure 53: View of the northern side of the Green

Figure 54: 71 Kew Green, an example of a high-quality frontage

Figure 55: The Cricketers public house

Figure 56: The cricket pavilion

Bush Road

Bush Road forms a further connector to the Riverside but has notably more formal character compared to Ferry Lane. This area originally had the ferry landing stage and housed a number of boathouses along the bank of the River Thames. The area has however greatly changed with the Ladies’ toilets forming the only surviving remnant of this area’s historic use. Presently, the area has modern buildings including a group of terraced houses found along Kreisel Walk – a cul-de-sac leading from Bush Road. This group has a distinctive red-brown brick with black aluminium windows. The houses have a mixture of flat parapeted and mansard roofs. The frontages have no boundary walls. The houses have substantial rear gardens that face the riverside path, but as the buildings are set further back, they don’t interfere with the river landscape.

Figure 57: Modern development on Bush Road

Figure 58: Bush Road in 1900s

Kew Green East Side

The east side of Kew Green has a distinctive change of character with terraced houses with more narrow plots prevailing, reducing the sense of grandeur and openness, and introducing a more intimate experience. There are still several 18th century buildings, particularly along the north side; however, there is a greater variation in age of buildings to this part of the Green due to its lesser proximity to Kew Palace and the Kew Gardens. This wealth of styles and the high survival of original detailing and character to each group form a significant contributor to the character and appearance of the area.

Glimpses of the industrial period of Kew can be observed in 112 Kew Green, a two-storey building facing Kew Bridge, built in 1964, that still preserves the sign of Caxton Name Plate MFG Co Ltd. and the metallic windows.

Nos. 68 to 110 are set at a lower level than the Green due to their proximity to Kew Bridge and the downward slope of the topography towards the River Thames. The terraced group is between two and three-storeys, with the majority constructed of stock brick. All the buildings address the pavement edge or are set back with only modest front gardens with decorative railings to maintain the consistent building line. Some of the buildings have small projections in their front gardens, like 106 Kew Green, which forms a remnant of a former shop front, illustrating the once commercial character of this part of the Green.

In the east part of the same group, Nos. 90 to 96 stand out from the building line with parapeted brick fronts. The Greyhound Kew Public House is particularly prominent within the streetscape due to its exposed timber frame façade and a detailed curved shopfront window.

There is a distinct roofscape to this group of terraces with a gradual step up of the roof line from west to east, and a notable prominence of chimney stacks, regularly spaced and breaking the skyline to add visual interest. The importance of chimney stacks continuous further eastwards with the grander buildings at the east end of the group. This includes a pair of Italianate houses at nos. 68 and 70 Kew Green, which are notably more distinctive with their rendered fronts, first floor cast iron balconies and deep bracketed eaves. The pair therefore stand out in the street scene.

Between Nos.66 and 68 there is a gap in development where the narrow lane of Kew Green Road extends north. There is a slight curve to the main road, with Nos. 52-66 set further back, allowing some sense of spaciousness to this part of the sub area. All the houses however still address the pavement edge or have modest front gardens, continuing the enclosed feel. Originally these houses were set behind a large grass verge; however, this has been largely removed and the area currently serves as a small car park, adding an uncharacteristic urban element to the area. Nos. 62 to 64 are early 19th century cottages, each two storeys high and two bays wide, faced in brick with slate roofs. No. 64 is recessed with a first-floor timber balcony with intricate fretwork. The pair were originally part of a group of three cottages of which No. 66 has recently been completely rebuilt.

At the end of the eastern side of Kew Green, as a group of three 18th-century cottages in yellow brick, Nos. 52 to 56 are set back from the main street behind a small grass path. These retain a high proportion of original features including their exposed timber window frames with 6 over 6 pane sashes.

Figure 59: Caxton building

Figure 60: The north side of Kew Green from Kew Bridge

Figure 61: 69 No.66 Green and path towards Westerley Ware

Figure 62: 19th century illustration of Nos.66,64 and 62 Kew Green

Just east of No. 52 the road branches into three: towards Cambridge Cottages to the north, Watcombe Cottages to the northeast, and Bushwood Road to the southeast. The group of Nos. 50 to a, b, c and d is a modern terraced group of three storeys, some with mansard additions, that is set back from this split in the road and faces Kew Pond, creating a transition between the Green and Priory Estate character area. This group is well designed for its setting, being unobtrusive with appropriate scale and sympathetic materials that fit into the predominant character of the area. They also continue the sense of enclosure and consistency that is prevalent in this part of the sub-area, with their stepped brick façades maintaining a regular rhythm of openings, with the first floor treated in a more elaborate manner.

Kew Pond is the predominant element of the north-eastern corner of the Green and serves as a natural division between the former Kew Village and the later development of Priory Estate. There is also a clear shift from the more austere Georgian terrace houses to more vibrant red brick detached houses which lie behind it to the east. The pond is one of the oldest historical features of the area and a significant mark in the landscape. The street parking on the west and north side has impacted on the historic appearance of the pond; it adds visual clutter which hinders the pond's visibility from the street.

The southeast side of the Green, which is divided by the main road, leads to Nos. 28 to 38, an imposing four-storey Victorian, red-bricked terrace group of houses, with the illusion of one single mansion building. It features brick pilasters and cornices between floors. The entrance retains its original double doors and features decorative masonry. Heading south, the buildings decrease to three storeys with a step variation in the roofscape, lined in a group of London red brick, with sizable front gardens. Boundaries are consistently low and visible so that front gardens are easily observed, creating a sense of openness, and contributing to a suburban garden character.

Nos. 2 to 4 Bank House, located on the east side of the road, is where the Palace Guard was located during George III's reign. It is a building of five bays with a projecting balustraded ground floor and two pedimented Doric doorways. On the west side of the A205, the buildings extend westward to Mortlake Road.

Figure 63: The east side of Kew Green

Street Furniture

Bollards

Black cast iron bollards are located around Kew Green and the west side of the Green, acting as a visual and physical barrier from residential and greener spaces and adding to the historic character.

Figure 64: Example of bollards in Kew Road

Benches

Wooden benches are spaced along the northern and eastern sides of the Green. They are in good condition and many are dedicated to local people.

Figure 65: Example of a bench on the Green

Railings

An iron railing fence surrounds the Green in different stages. A white iron fence with a white timber gate flanks St. Anne's Church and around Kew Pond as well as the east side of the Green.

A black iron fence surrounds the west side of the Green, between the bridge and the lower level of Kew Road. Most of the Green have low fences, thereby preserving the open space atmosphere.

Fiugre 66: Black iron railings around the Green

Figure 67: White railings on the eastern side of the Green

Character Area 3: Riverside

Summary Description

The riverside path provides a green and peaceful aspect to the Conservation Area. There are broad views created by the bend in the River Thames, which are particularly dramatic looking towards Kew Bridge.

The east side of the path is lined by small terraces of 19th century cottages with open spaces – a playground, communal greens, an allotment, and a bowls and tennis club, providing an attractive domestic setting to the towpath. At the recreation ground, the view is set to the River Thames rather than the Green, and there are links inland from the pier. There are also views of the north bank along this stretch and its remarkable group of historic houses in Strand-on-the-Green.

In contrast, the area to the west of the bridge contains 20th century flats, though these are surrounded by greenery of the riverside and deep rear gardens. This adds to the open and more rural character to this part of the riverside. There is also a distinct sense of separation between this part of the riverside, both physically and visually, with only limited connectivity to the Green, in addition to the tall walls of the Herbarium and Kew Gardens forming a physical barrier. From the towpath, the curve of the River Thames however allows for wide and changing views across to the north banks.

There are a few examples where the fronts of the houses in Cambridge Road have been altered or painted in an unsympathetic manner, but the majority are well-preserved and maintained. The most obvious change is to the backs of Bushwood Road where the roofs have large box dormers, which are out of character with the buildings and the Conservation Area.

Kew Pier provides a focus for the view on the towpath east of the bridge. The row of boathouses fronts directly onto the riverside path and berth on Oliver's Island. These are significant reminders and links to the history of fishing in this area.

Townscape

Riverside East

The majority of built form on the east side of the Riverside is contained within a grid pattern of streets with two-storey terraced cottages east of Thetis Terrace. These form an attractive group, the more modest scale of which is unique to this part of the Conservation Area. The rural domestic character of the group is complemented by the footpaths from which many of the cottages are approached, not having front gardens and the facades facing onto the street. This results in a highly enclosed feel to the street scene. The rear gardens are glimpsed through the area, with mature gardens that soften the character.

The cottages located on Thetis Terrace and Willow Cottage are situated on narrow streets, with front gardens facing Westerly Ware Park. The cottages are an identical group, two storeys, with a canted bay on the ground floor and a red brick façade, with the exemption of No. 4, which has a rendered white façade. Although a good distance from the river, the buildings are not facing any road or the river path but instead, are facing the green open space that provides Westerly Ware Park, making this group of houses the only ones that are not facing a road.

Cambridge Cottage s form another largely consistent group of cottages, which are set on parallel streets. The cottages are simply designed with arched entrances to inset porches.